Hot dogs and frankfurters took different paths through history and tradition. One became American folklore, while the other stayed proudly European. Let’s rewind time and trace how a sausage sparked a surprisingly rich culinary divide.

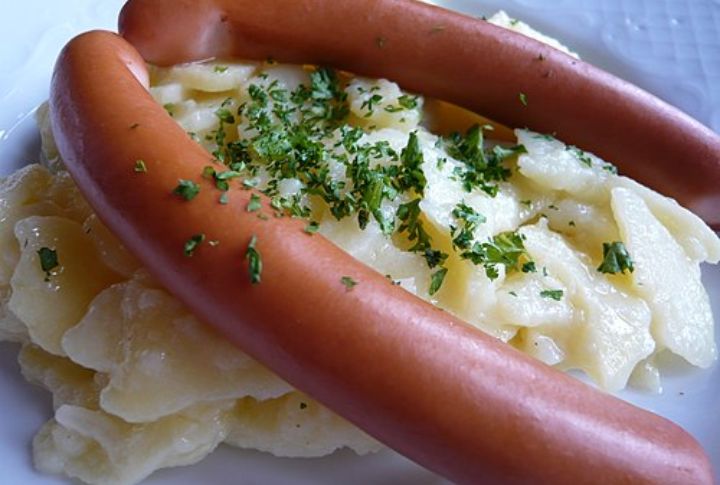

Frankfurt’s Meaty Legacy

In Frankfurt, sausages aren’t just food. They represent tradition passed down through generations. The Frankfurter Wurstchen, protected under EU law since 1929, must be made in or near the city. Served with bread and mustard, this pork sausage carries centuries of local pride in every smoky, slender bite.

A Street Food Twist In Coney Island

In 1867, Charles Feltman began selling sausages in buns from a cart in Coney Island. It marked a turning point in how food was served and consumed. Immigrant ingenuity met convenience, and the hot dog was born. What started as a seaside snack quickly became an American food icon.

The Bun Changed Everything

Long before ketchup debates, it was the bun that made the difference. Offering one-handed portability, the bun lets sausages leave the dinner table and hit the streets. That simple shift, pioneered in Brooklyn, turned a European staple into an American street food revolution.

What’s Inside?

Traditional Frankfurters (Frankfurter Wurstchen) use finely ground pork and smoke it to develop flavor. Though also smoked, hot dogs are usually emulsified and can contain beef or poultry. These methods shape texture and how each sausage responds to heat and preparation styles.

July 4th Vs Oktoberfest

On July 4th, Americans consume over 150 million hot dogs. Oktoberfest in Munich features hundreds of thousands of sausages, including frankfurters. These events reflect more than appetite. Sausages at both festivals carry cultural significance, which form part of national rituals rooted in tradition and collective celebration.

When Labels Get Messy

The USDA allows “frankfurter” and “hot dog” to be used interchangeably, provided the product meets defined standards. This overlap creates public confusion. What seems like a simple naming issue is a federally sanctioned ambiguity that blurs the lines between two culturally distinct sausage identities.

Two Sausages, Two Identities

In Frankfurt, sausages are served with bread and mustard, with no frills. In Detroit, the Coney Dog comes loaded with chili and onions. These serving styles reflect more than taste, which reveals how each city imprinted its culture onto the sausage it calls its own.

Are They That Different Nutritionally?

Some Los Angeles diners view frankfurters as the purer choice, but nutritional facts challenge that belief. A pork frankfurter contains roughly 150 calories and 13 grams of fat, while beef hot dogs come close in value. Both are high in sodium, which narrows the gap more than expected.

Sausages In Wartime America

During World War I, anti-German sentiment led to the term “frankfurter” falling out of favor in the U.S. Vendors and newspapers began using “hot dog” more widely to avoid German associations. This shift reflected how politics shaped what Americans chose to eat and say.

Beyond The Name

At Yale in New Haven, linguists study how language influences perception. As American preferences shifted, the word “hot dog” gradually replaced “frankfurter.” This transition affected more than terminology by shaping public expectations to show how names can quietly transform people’s thoughts about everyday food.

Leave a comment