It starts with curiosity. Why does this one taste rounder? What’s different about that label? You follow those questions down a rabbit hole of rules and unexpected insights. Eventually, bourbon isn’t just something you drink. Let’s walk through the stuff most drinkers overlook, but seasoned fans can’t unsee.

The Five Bourbon Rules

Bourbon is defined by strict legal standards. To qualify, it must be made in the U.S. with at least 51% corn, aged in charred oak barrels, distilled at less than 160 proof, and put into the barrel at 125 proof or lower. Plus, it must be bottled at a minimum of 80 proof—no exceptions.

New Vs. Used Barrels

Wine in old oak is a whisper. Bourbon in fresh char is a full-on conversation. By law, bourbon barrels must be new and charred. Reusing barrels is for rum or Scotch. In bourbon, that fresh oak gives it depth with caramel and toasted vanilla in every sip.

Not All Are Straight

“Straight bourbon” shows up on more bottles than you think. But it’s not just a fancy label. It guarantees at least two years of barrel aging with zero additives. If that word’s missing, it still might be bourbon, just with less aging and no promise of how clean the process was.

Charred Barrel Science

Some spirits flirt with oak, but bourbon goes all in. Inside the barrel, fire creates a charcoal layer called “alligator char.” It’s not just for looks. That scorched interior caramelizes wood sugars and acts as a natural filter, slowly shaping bourbon’s vanilla-rich identity over the years.

Kentucky Isn’t Mandatory

The old saying goes, “It’s not bourbon unless it’s from Kentucky.” But that’s like saying sparkling wine isn’t real unless it’s French. Hudson Whiskey in New York and Breckenridge in Colorado are just two examples proving otherwise. Bourbon is federally defined, not state-bound. Kentucky’s iconic, but it’s not exclusive.

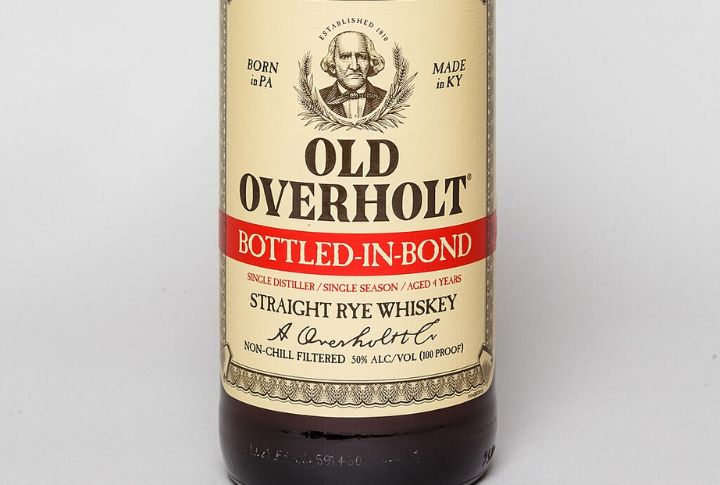

Bottled In Bond Basics

In wine, provenance matters. In bourbon, bonded bottles offer the same assurance. Born from an 1897 act, they require a single distiller, one distilling season, four years in barrel, and a final cut at 100 proof. Its structure and clarity are wrapped in a simple phrase.

Wheated Bourbon Flavor

Pull a cork on a wheated bourbon, and you’ll know the difference right away. Wheat softens everything. It dials down the spice and lets fruit and honey come forward. It’s no accident that some of the most beloved bourbons on the shelf use wheat instead of rye.

Age Doesn’t Equal Quality

In the wine world, aging is complex. The same goes for bourbon. Older doesn’t always mean better. Time can add character, but it can also overwhelm. Tannins from the wood take over if left too long. Some of the best pours are young and unexpectedly balanced.

Single Barrel Standards

A single barrel stays in one exact spot as it ages, and that position shapes its flavor. Barrels higher up in the rickhouse get more heat, speeding up aging. Lower ones stay cooler and develop slowly. No blending means each bottle reflects its own unique aging conditions.

High Rye Explained

Rye changes the game. In a bourbon mash bill, more rye means more spice and less sweetness. Think dry finish and citrus edges. High-rye bourbons feel leaner and livelier. For drinkers who love structure and boldness, this is where things start to feel familiar.

The Devil’s Cut Explained

After the angel’s share evaporates, what’s left inside the wood stays locked away. That trapped liquid is the devil’s cut. It doesn’t end up in most bottles, but distillers have ways of extracting it. It’s stronger and a bit more intense, like bourbon’s last secret hiding in the barrel.

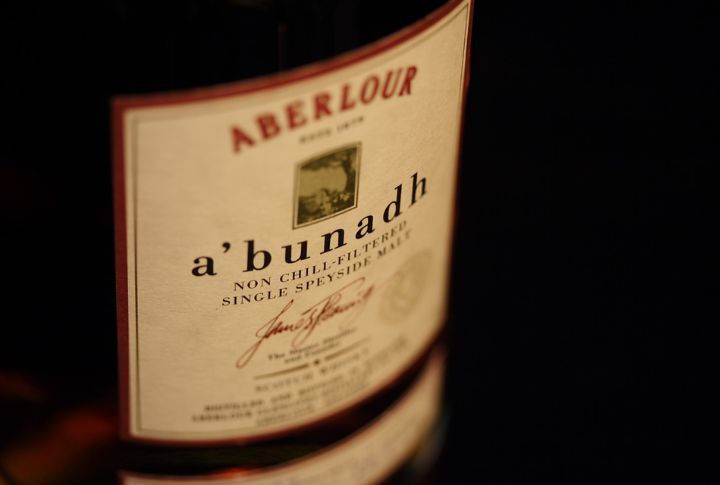

Chill Filtering Debate

Do you ever see a bottle labeled “non-chill filtered” and wonder why it matters? Chill filtering removes fatty acids and esters that can make bourbon cloudy when cold. It also strips out texture and subtle flavors. Fans argue that filtration cleans up appearance at the cost of complexity.

Small Batch Myths

Small batches sound romantic, like limited quantities and handmade crafts. In reality, there’s no legal definition. Some brands blend from 10 barrels, others from 200. It’s a marketing term that varies wildly across distilleries. Quality isn’t guaranteed by the label. It all depends on who’s behind the blend.

Barrel Rotation Traditions

Some distilleries rotate their barrels during aging. Others don’t touch them. Rotating can even out differences in heat and airflow, but it also interrupts the natural aging process. Letting a barrel stay put allows for more variation. And for many, that variation is the beauty of bourbon.

Barrel Proof Bottles

Barrel-proof means nothing’s watered down. What comes out of the barrel goes directly into the bottle with all its original strength. That might be 110 or even 130 proof. It’s bold and often a bit wild. But it also gives full control to the drinker, one drop of water at a time.

The Sour Mash Process

Sour mash helps bourbon stay reliable. It reuses a portion of the old mash to regulate acidity and control microbial growth. Without it, fermentation can get unpredictable. It’s one of those quiet processes that shapes nearly every bottle you see.

Water Makes A Difference

Just a splash, that’s all it takes. A few drops of water can create aroma compounds trapped by high alcohol. It softens the edge and opens up subtler flavors. While some purists prefer neat pours, many distillers suggest water as part of the tasting process. It’s not dilution. It’s discovery.

How To Smell Bourbon

Aromas carry half the story. Stick your nose in the glass, and the alcohol can numb it. Hover above instead. Inhale with your mouth slightly open. Try one nostril, then the other. The way you smell affects what you actually pick up in the glass.

Why Glassware Matters

Set two bourbons in different glasses, and you might think they came from different barrels. That’s the power of shape. A wide tumbler diffuses aroma. A tulip-shaped glass draws it in. Even mouthfeel shifts depending on how the bourbon hits the tongue. The presentation changes perception.

The White Dog Phase

Every bourbon starts as a clear spirit known as a white dog. It’s distilled below 160 proof and enters the barrel at no more than 125. Without oak, it’s sharp and grassy, but it holds the mash’s fingerprint. Distillers taste it to judge the foundation before wood changes everything.

Leave a comment